Dear Blog Readers,

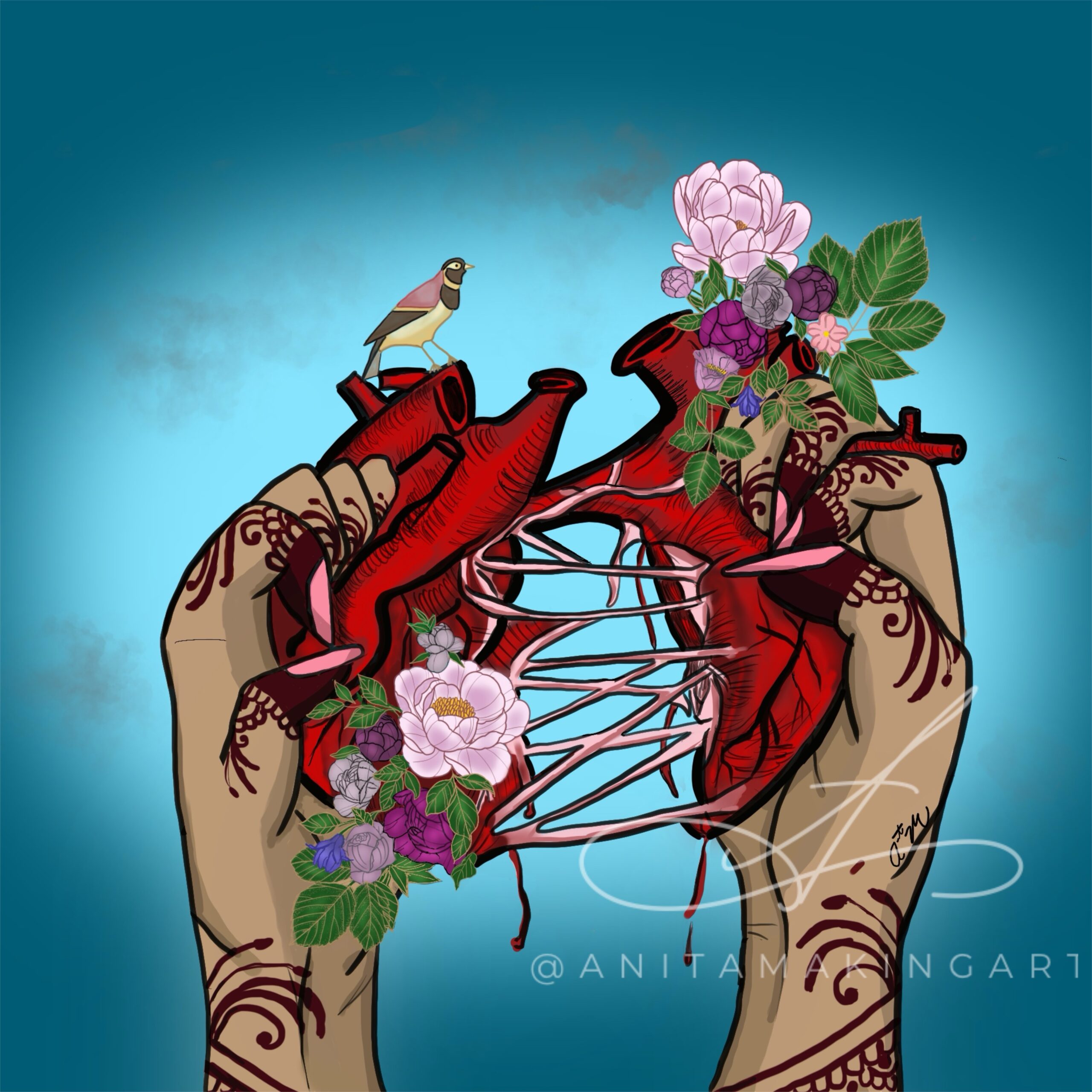

Here is our next artist in our To Be Seen series: Anita Majumdar

I started seriously exploring illustration when I was about 12 or 13, creating a series of comics I called “Suzy Q” about a small baby girl with red hair and her dim-witted brother and also made comics in place of birthday cards when I was in university. Then I started exploring portraiture of South Asian women more intensively but didn’t have proper supplies to explore smudging and shadow and highlight the way I wanted to, so I used my mom’s old eyeshadows instead and used drugstore hairspray to set it in place. Eventually I managed to get my hands on charcoals and pastels.

My main profession for the last two decades has been in theatre as an actor, playwright and dancer, so when I graduated from the National Theatre School of Canada, I put visual arts practice away to focus on my acting career.

Almost 2 decades later, the pandemic hit and theatres closed, I decided to teach myself digital illustration so I could keep making art in some way. It turned into falling back in love with illustrating.

I missed having a connection with an audience, I made myself create one new piece a week and posted it to my Instagram account and slowly started building a new community of like-minded artists of colour from around the world. We shared tips and stories and it became a catalyst for me to keep exploring and pushing my skills and knowledge further. Soon I started getting commission and collaboration requests, one of which was “Shakespeare’s South Asian Ladies” commissioned by The Shakespeare Company and Hit n’ Myth based out of Calgary where I reimagined Shakespeare’s leading ladies under a South Asian gaze. It received an exhibit at the Rose Theatre.

Growing up there wasn’t a lot of representation of South Asian women in mainstream media. In a lot of ways, I think that’s maybe why I became an actor. I think the absence of seeing yourself (your race, your ethnicity, the colour of your skin) associated with beauty really impacts a generation and their relationship to their bodies and taking up space with their unique beauty. So my work for the most part features women of colour, with an emphasis on hybrid portraits of South Asian women; mixing surrealist concepts against a backdrop of realism.

I really believe in the work that Sheena’s Place does and how accessible they make their work for people who need and want support. When I saw the call for artwork, I thought this was a way of marrying the very real things I struggle with and the art I make in response to managing those struggles.

Hope is such an important component of my work and that’s how I interpreted the theme. While my piece doesn’t unnecessary scream “hope”, I think it reflects my personal experience of the moment of acknowledging the problem, calling it by its name and seeking help.

When I was really little and had to draw myself in elementary school, I drew myself with blonde hair and blue eyes. I thought that’s what it was to be beautiful and I wanted to be beautiful. I didn’t realize internalized racism and an undiagnosed learning disability was contributing to my own erasure. Art was the only place where I could be honest with myself, laugh at myself, and really be comfortable in my skin. It seemed to be the only way that I could both describe the world I lived in and the world in which I wished to live at the same time.

For me, having the vulnerability to take personal truths that were once in shadow and bringing them to light.

[Tell me about a time when you felt seen]. The moment that comes to mind is in grade 10 drama class, at the end of the year we all had to do a monologue and perform it in an evening show for our friends and family. I chose a monologue from legendary Canadian playwright Judith Thompson’s play “I Am Yours”, and played Mercy, a woman who struggled deeply with her self-worth when it came to romantic attention from men. I was a pretty inexperienced actor at that point to play such a complex role, but the problem wasn’t that I couldn’t relate Mercy (absolutely I could!); the problem was trusting myself to be really vulnerable with a live audience and offer a part of myself that felt embarrassingly real.

On the evening performance night, I don’t know what came over me, but it was like switch flipped and all the hurt and rejection I had felt flooded into through Judith Thompson’s words. I could feel the audience truly witnessing not only what I was saying but the felt experience of what was unsaid.

When I got off stage and met up with my parents, my dad was floored. He never really understood why I wanted to go into acting (because wasn’t very good in anything he had seen me in), but that night I think that performance expressed something to him both about my ability to act, but more importantly something I had felt but could never express and it really changed his perception of me. It was one of those moments on stage where I could energetically feel I had earned an audience’s attention by simply being honest. Dropping the façade of “acting” and really just channeling my lived experience out there for all to see.

It’s probably why I pursued acting/theatre over visual arts initially, because “being seen” is built into the medium. With visual art, so often you’re not in the room with the viewer unless you’re lucky enough to exhibit your work. People enjoy your work privately and but only learn how it made them feel it they reach out to you, which is why posting my work to Instagram was so helpful. I could connect with audiences really easily in a way I never had before.

Whether it’s writing plays or acting on stage or painting a portrait, it ultimately always comes back to story: what’s the story I’m telling? This sounds silly, but to tell a story honestly, for me, means being in really comfy clothes, cozying up under a blanket and my favourite pillows and getting down to work. I often have my favourite tv shows that I’ve binged 100s of times on in the background or listen to music or a good podcast. Keeping myself physically comfortable I’ve learned is important because the mental activity it requires to make art is so deeply uncomfortable for me. Pushing myself to try new things I’ve never done before and not knowing if I can successfully execute it. But to take the risk and try anyways I think takes courage.

I have a pretty tenuous relationship with perfectionism, and so accepting my work won’t be perfect but that it’s still worth trying is the thing I’m practicing every time I sit down to draw. And inevitably I learn something with each piece I create which pushes my skills further.

In a way, I’ve had to really learn self-care to keep making art so I didn’t self-destruct.

The connection [to Eating Disorders] is indirect, in that I draw women of colour in ways that are aspirational tempered with honesty. Spending that much time with the smallest of details of someone’s face or body has given me new appreciation. Something I might have considered a flaw before, Anita the artist gets excited to draw and explore its human- ness. The texture of skin, the shadows on the lines of a body or fabric that holds in a body… it makes the person you’re looking at more real, more like someone you know and could talk to. And I think at this stage in my life, I’m no longer interested in perfection in art, which helps me with my relationship to my own body.

In my earlier years, I wanted to make people feel or cry when engaging with my work. As I get older, I realize I can’t impose my desire onto someone else’s experience. All I can do is offer what I have to say in the ways I’ve chosen to say it and hope when someone sees it they’ll acknowledge that it comes out of the artist being honest and thoughtful about their lived experience, without the pressuring the viewer to identify with it too.